British Sword Makers

The history of British sword manufacture is a tale characterised by a series of economic highs and lows, due in part to the changing necessities of military conflict, government intransigence, and an on-going “war” conducted by British sword makers, against a flood of cheap, (sometimes inferior) foreign imports, most notably from Solingen, Germany.

Price Competition

For most of the nineteenth century, this inability to compete on price with Solingen ensured the steady decline of British sword making and the resulting emergence of only a small number of companies who were able to trade more on quality than price. The most notable of these was The Wilkinson Sword Company. Henry Wilkinson never claimed that he could produce a cheaper sword, but through rigorous testing procedures and innovative blade design, he could certainly rightly claim that his swords were of world-beating standard. In 1900, the German sword trade could sell an officer’s sword to a London retailer for 21 shillings (£1.05), who would then sell on the sword at 30 shillings (£1.50). If you wanted to buy a Wilkinson “Best proved sword, with a patent solid tang”, a customer would be asked to pay 5 guineas (£5.25). The price difference is staggering but it is a testament to the high regard in which these swords were held by contemporaries that they were still purchased in such large numbers.

Combat Reliability

It took many years for the military authorities to grudgingly accept that if you paid a little more for better quality, home manufactured blades, then the critical issue of combat reliability could be properly addressed. The axiom that you get exactly what you pay for could have been etched, literally, on the blades of many swords purchased by the British Army. Indeed, there were times when swords supplied to the British Army were regarded as practically useless when wielded in the heat of battle. Reports from both officers and men detail constant service problems with broken and bent blades that, in some circumstances, led directly to the unnecessary deaths of servicemen. The actual quality and design of swords carried by British soldiers had always been a bone of contention and, in typically British fashion, led to the establishment of numerous Committees of Enquiry, following a series of very public sword scandals.

Feast and Famine

British sword makers and their myriad suppliers lived through frequent periods of economic feast or famine. The availability of regular work was particularly erratic and many companies went in and out of business with alarming regularity. The Napoleonic Wars of the late-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries brought some stability. It became a temporary boom time for sword making and its allied trades, with government contracts placed for thousands of swords, bayonets and guns. The city of Birmingham was a major beneficiary of this government contracts placed for thousands of swords, bayonets and guns.

Sword Workshops

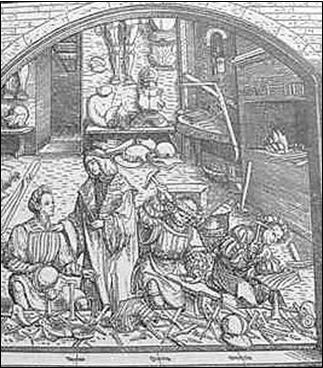

Individual craftsmen and women (mainly anonymous) were the real sword makers. In many cases, they provided the finished parts to the “sword maker” who then simply assembled and sold on to the retailer the finished sword. During the early 1800’s, countless small workshops and homes turned out blades, grips, scabbards and mounts. Their identities will probably never be known as the “sword maker” or retailer invariably stamped the completed sword with his own company name, but their superb skill and artistry is thankfully passed down to us in the fine pieces that are now available to the collector.

Cut or Thrust?

It should also be remembered that the history of British sword making was driven by great theoretical debate and argument. The fundamental question that ran through the design and development of British swords, namely that of whether a military sword should be primarily one of cut or thrust, rumbled on for many years. It actually took over one hundred years of trial (and mainly error!) for this debate to be properly satisfied. By then, the conclusion, that a thrusting sword was the most effective, had become completely irrelevant in a new world of machine guns and static warfare.

Origins of British Sword Manufacture

Let us first take a look at the historical origins of indigenous British sword manufacture.

The recognition of sword-making in Britain as a distinct trade can be traced back as far as 1415, when The Worshipful Company of Cutlers of London received Royal Assent. The metal producing area of Solingen, Germany, followed this trend later in the century when the ruling council in Cologne granted permission for a guild of swordsmith and cutlers to be established. The sixteenth century saw the genesis of a more organised method of sword manufacture in Britain. Henry VIII initiated a thriving armoury at Greenwich, London. It turned out some remarkable pieces of armour and edged weaponry and these can still be seen today. Even at this very early stage of the story we run into the interminable thorn in the side of British sword manufacturers. This concerned the use of imported skilled German craftsmen from Solingen and Passau, who were employed in King Henry’s armoury, due to a severe shortage of skilled English workers. Although it might seem highly contradictory, at least German workers were producing “English” swords in England, rather than in their own homeland.

For the next three hundred years there would be bitter competition between German sword makers and the small English manufacturers, to win the custom of sword buyers (both civilian and military) within Britain. It was a competition in which Germany would be the ultimate victor.

German Immigrant Sword Makers and Hounslow

Following the influx of German Protestants into England due to Catholic religious persecution in the 1600‘s, a number of skilled German metal workers helped to establish a new sword factory in Hounslow (near London), in 1620.

Shotley Bridge Sword Makers

The Hollow Sword Blade Company was also formed in 1690 at a new northern factory in Shotley Bridge, County Durham. The choice of location was due to the rich iron ore deposits found in the local area, the fast flowing River Derwent that was ideal for tempering blades, and also the fact that its remoteness was handy in keeping the secrets of manufacture away from prying eyes, e.g. competitors. An interesting local story highlights the pride with which these newcomers viewed their enterprise.

“There is a story that one of the Shotley sword-making fraternity, a certain William Oley, was once challenged by two other sword makers to see who could make the sharpest and most resilient sword. On the day of the challenge, the three men turned up, but it seemed that Oley had forgotten to bring an example of his work. The two other sword makers, assuming that he had been unable to make a sword of a suitable standard, began to boastfully demonstrate the strength, sharpness and resiliency of their workpieces.

Eventually their curiosity got the better of them and they asked Oley why he had not brought a sword. With a mischievous grin, Oley removed his stiff hat, to reveal a super-resilient sword, coiled up inside. He challenged the other two sword makers to remove the sword from the hat, but their attempts nearly resulted in the loss of their fingers. In the end the sword could only be removed by means of a vice. For strength, sharpness and resiliency Oley’s sword was undoubtedly the winner.”

One of the Hounslow founders, Benjamin Stone, confidently declared that he had “perfected the art of blade making”. His swords were “as good and cheap as any to be found in the Christian world.”

Hollow-Ground or “Colichemarde” Blades

These boastful claims were soon to suffer ridicule when it was found that Hounslow and Shotley Bridge could not reproduce the quality of manufacture that was coming out of Germany, particularly in the lucrative area of hollow-ground or ‘colichemarde’ blades used in smallswords, which had become the standard dress arm for both gentleman and military officers. Solingen had also developed specialist machinery for the production of these blades, which involved rolling out the hollows of the blade. It was a revolutionary technique and cut down dramatically the standard dress arm for both gentleman and military officers. Solingen had also developed specialist machinery for the production of these blades, which involved rolling out the hollows of the blade. Both Hounslow and Shotley Bridge had nothing like this and could only manufacture by labourious hand crafting of the blade. Rate of production was tiny compared with the established German sword guilds.

Despite the imposition of heavy taxes by the British Crown on the importation of foreign blades in order to stimulate home production, Hounslow and Shotley were only able to produce simple, flat bladed weapons, rather than the more sophisticated swords being manufactured in Germany, and it soon faded into obscurity. A typical “Hounslow Hanger” of the late-seventeenth century is now an extremely collectable genre of sword.

Importantly, the secret knowledge of how to hollow- ground blades rested primarily in Germany and determined attempts were made to bring back that technology to England, including an unsuccessful invitation for German smiths to come and settle in England and teach native workers. A English patent was granted in 1688 for the production of hollow ground blades but progress was slow, due mainly to the unsettled political environment in England.

Shotley did not appear to turn out many hollow-ground blades and within a relatively short period of time the group of businessmen who started the enterprise sold out to one of its employees, a certain Herman Mohll. The name Mohll or the anglicised Mole as it was to later become, deserves a special place in British sword-making history as it is synonymous with the manufacture of British swords, particularly those service patterns supplied directly to the British Army.

The first of Mohll’s hollow blade ventures at Shotley Bridge soon ran into trouble with British Customs, due to his involvement with a cargo of smuggled, partly finished, hollow- ground blades from Germany, that he planned to retail as his own. We then next see him starting up another company, Herman Mohll and Son, which concentrated on the manufacture of military blades.

This he eventually sold out to Robert Oley (nee Ohlig), in 1742, who carried on the business until 1832 when Robert Moll, a descendant of the original family, bought back the firm, and changed the name again to Mole. They continued as a military contractor of swords and bayonets until being subsumed in 1922 by the Wilkinson Sword Company.

It is interesting to see that Shotley Bridge had high ideals when it came to proclaiming the quality of their blades and even impressed a running horse mark to blades in imitation of the running wolf marks seen on Solingen / Passau blades. Shotley Bridge has interest for the student and collector in that it was a historical starting point for British sword manufacture rather than a beacon of technological and artistic prowess. For that we need to adjust our gaze to the cities of London and Birmingham.

LONDON

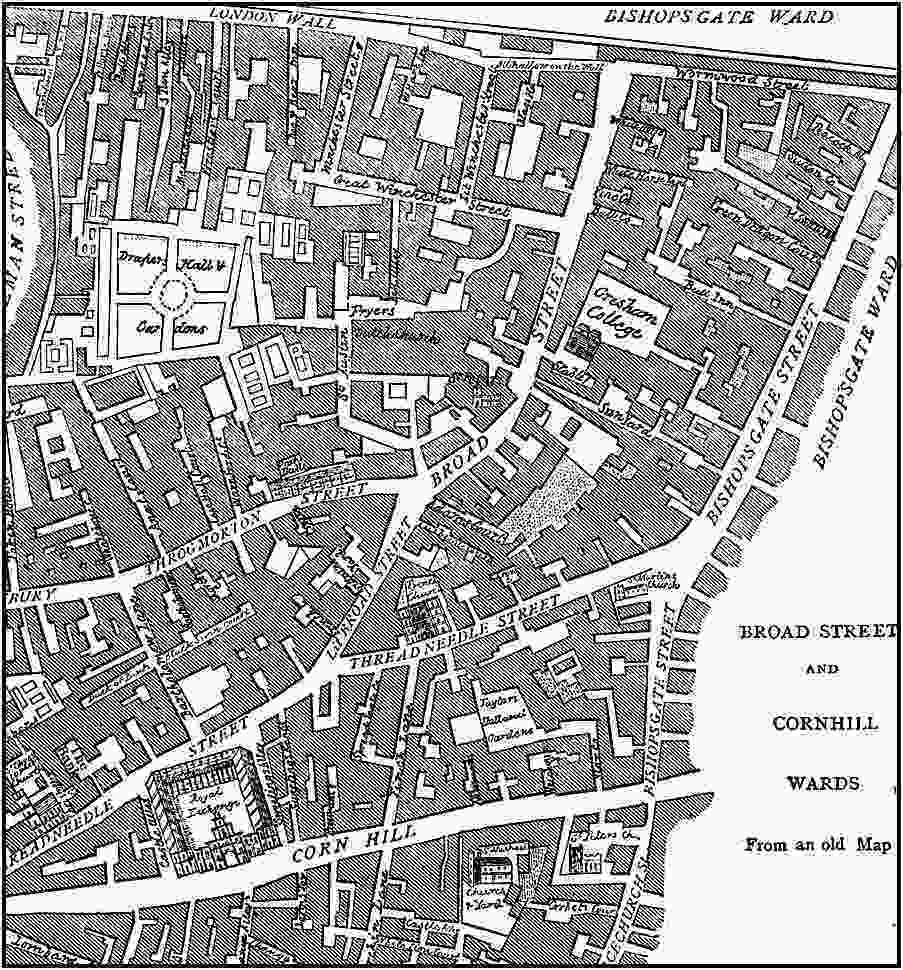

Up until the late eighteenth century when Birmingham took over the primary role of service sword manufacture, London was at the centre of both sword making and retailing. It was an obvious choice due to some basic geography. For hundreds of years, it had been a port of entry and exit for manufactured goods to the continent. Countless sword blades were brought over from Germany and either decorated or mounted to London-made hilts and scabbards. They were then shipped out, most notably to the fledgling United States, where the eagle-head sword is commonly found with an English maker mark. Many craftsmen were involved in this process and London carved out a justifiable name for herself during the eighteenth century, particularly in the manufacture of silver-hilted smallswords. Those collectors lucky enough to acquire these exquisite swords, will invariably see a London silver hallmark to the hilt (if not rubbed away) and, if luckier still, the initials of the maker are sometimes present. The work of Leslie Southwick (London Silver-Hilted Swords) has made tracing original London sword silversmiths considerably easier and I fully recommend this exhaustive book on English silver-hilted swords.

Names that the collector of British military swords will be familiar with include many London makers and retailers such as John Prosser, Samuel Brunn, Nathaniel Jeffreys, John Salter, Henry Tatham, Francis Thurkle and, of course, Henry Wilkinson.

The sword and cutlery trade was based primarily in the City of London and included such locales as Cheapside, London Bridge, and Fleet Street. Prestigious addresses such as the Strand, Piccadilly, Bond Street, and Pall Mall acted as both manufacturing locations and retailing hubs. Many of the sword retailers and makers became very wealthy and subsequently moved out of the centre of London to more leafy and cleaner areas, although a sizeable number of dedicated sword makers tended to live and die in their original neighbourhoods.

John Salter retired to the comforts of Bexley, Kent and Nathaniel Jeffreys left the City for distant Worcester.

Special mention must also be made of one notable character in the London trade during the Napoleonic period. His name was John Justus Runkel and his is one of the most frequently observed signatures to be found on British military swords of that period. J.J. Runkel, was a German immigrant who became a British subject in 1796. He proceeded to almost corner the market in the large-scale importation of sword blades from Solingen, Germany, via the port of Emden. In the first years of the nineteenth century he was said to be handling hundreds of blades every month. No wonder so many are still available to the collector.

He did not involve himself in the actual manufacture of swords, but was purely a conduit or agent for German blades entering into London. They came as either plain or decorated blades with blue and gilt applied in a standard format. Look at a number of Runkel blades together and you will see that the motifs are all very similar and seldom vary. Runkel was catering for an early form of “mass-market”, and the British officer purchasing a Runkel blade would not find too many surprises. That said, a blue and gilt blade by Runkel retaining most of the original colour is still a very attractive piece, and we should be glad that a reasonable number have survived.

In contrast to the Birmingham trade who produced most of the plain service swords required by the ordinary soldier, London was noted for her skill in combining the art of the jeweller, leather worker and blade decorator. Many presentation swords, particularly those made during the Napoleonic Wars, were of London origin. Andrew Mowbray, in his book on American Eagle-headed Swords (The American Eagle-Head Pommel Sword), remarks that London was regarded as producing a higher standard of fire-gilt finish to blades than those seen in Birmingham, and that a London blade could be recognised purely within that criteria.

London sword makers enjoyed a flourishing trade within Britain and on the continent for many years. It was only after the 1820’s, and the re-emergence of Solingen, combined with economic depression at home, that we see a dramatic reduction in the capital’s ability to re-capture past sword-making glories.

Nineteenth Century

As we move into the nineteenth century, the British Army realised that there was an urgent need for better standardisation of production and quality within the issue of swords. This led to the belief that a manufacturing facility, based in Britain and better controlled by the military authorities, was an urgent necessity. A Board of Ordnance had already been set up since the seventeenth century with the job of overseeing the standard of arms produced for the monarch’s forces. There was a system of inspection within the Tower of London but improvements were needed and, in 1804, the Board of Ordnance established the Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock, north of London. It was later to be designated the Royal Small Arms Factory and became a major supplier of guns, swords and bayonets to the British Army. Despite this, it was still unable to produce the very large numbers required by the expanding British armed forces and contracts were regularly shared with British and German commercial sword makers. This can result in the collector encountering both British and German makers’ marks to one particular pattern of sword, unlike the dedicated French government sword makers at Klingenthal or Chatellerault, whose blades are consistently marked with the names of these two famous French domestic government armaments factories.

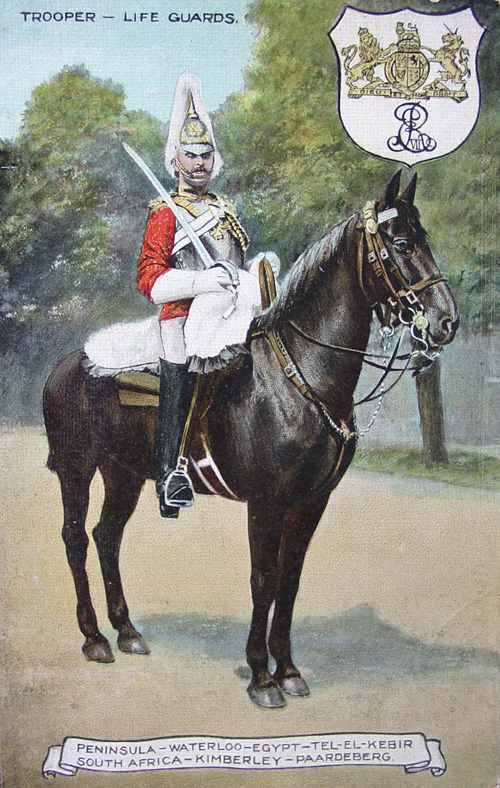

A typical 1853 Pattern Cavalry Trooper’s sword might be seen with both Enfield, Mole and Kirschbaum (German) makers marks

It must also be remembered that many London cutlers had workshops or agents in Birmingham and this situation was reciprocated with the Birmingham trade. Towards the end of nineteenth century, the number of actual sword makers, rather than retailers, in London, had greatly diminished. Great names such as Prosser, Salter and Tatham had long gone and companies such as Wilkinson, Thurkle and Gaunt were left to splutter on until the early years of the next century. Only Wilkinson Sword survived after 1930.

© The History of the Manufacture of British Swords article by Harvey Withers – militariahub.com

Not to be reproduced without prior agreement.

DO YOU COLLECT ANTIQUE SWORDS?

DO YOU WANT TO KNOW THE VALUE OF YOUR SWORDS?

IF SO, YOU NEED TO PURCHASE THESE FULL COLOUR BOOKS!!

CLICK IMAGES TO BUY YOUR SWORD BOOKS!!